If you’re a regular user of BoardGameGeek, the website that encapsulates the state of the board game hobby better than any other, you’re well aware of some well-established trends.

The first, and the one that perhaps shapes new entrants to the hobby, is that the games that end up in the top rankings in the vaunted Top 100 tend toward complexity. The top games for as long as I can remember (we’re talking back to 2012 or thereabouts, though, not to the founding of the site) have been interesting games with several intertwined mechanics. Even the more approachable games on the list tend to start at simpler levels and progress toward more complicated ones.

This is not a slight against games of that sort, nor is it a slight against the website. It’s simply a reflection of the fact that it’s a site for enthusiasts, and enthusiasts tend toward heavier games. It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, but it’s true in any hobby. Consider photography as a hobby: When I first started taking photography seriously, I used a starter digital camera with an attached lens, then I moved toward a starter SLR with a kit lens. Today, I exclusively use older manual focus lenses adapted to a modern mirrorless body.

It’s a clear progression, and while not every hobbyist will follow that same progression to its natural ends, plenty will, and they will congregate in spaces together. I think that’s a great thing. Whatever you think of the site, BGG is a resource that has helped hobbyists congregate. (It’s also a great, encyclopedic resource, and I love it for that.)

The second well-established trend worth noting: Enthusiasts and hobbyists tend to focus on new entrants to said hobby. Gamers tend to focus on games just released. There are plenty of reasons for that, but for me, it’s that designers are creating games that do things in interesting, unusual ways. Take Fromage as one recent example: Yes, there are a lot of worker placement games, but there are few worker placement games in which you’re placing the workers simultaneously on a rondel. That’s unusual, and it builds on so many concepts that came before. That’s one of the beautiful aspects of board games.

But all of this can prove difficult for some of the people with whom you’ll play games. The excitement of new games and new ideas is alluring. Complicated, involved games might engage parts of the brain you’re not using when playing simpler games. Building on top of concepts you already know and appreciate is invigorating, and the feeling of expertise is one that holds a certain allure for so many of us. We could spend days, months and years wondering about the causes, but I don’t think it’s particularly germane to what I’m trying to argue here, so we don’t need to go too deep into it.

The growth of the board gaming hobby has perhaps given many of us, myself included, an inkling of an incorrect assumption. The growth of the hobby does not preclude the fact that many aren’t interested in becoming experts in gaming. Simply because there are better lightweight games than we have seen in previous decades, we should not expect players interested in casual gaming to naturally progress toward heavier gaming. Some will, but with all hobbies, there’s a narrowing of the group when approaching expert-level involvement. That’s no bad thing. I’m not, for instance, into 18xx games (although I’m open to it, if anyone wants to teach me). This newsletter isn’t about heavy games, particularly, and that’s not because of some audience concern — it’s because my passion lies elsewhere.

But all of this doesn’t mean that we can’t or shouldn’t find ways to engage in hobby gaming with those outside the hobby. I would only argue that it’s important to consider how lightweight, casual games can offer you opportunities to engage meaningfully with people to whom you’re close. Gaming, for me, comes down to one fundamental idea: I have opportunities to engage in play with other people. Sociologists have written about the importance of play since the foundational moments of sociology, and plenty have argued that play is fundamental to culture. I’m no sociologist (I took a few classes in college, perhaps in part due to a hesitancy to graduate with a meaningful degree. I don’t regret my Bachelor of Interdisciplinary Studies, to be clear. But my career is not particularly related to my degree.)

There’s a reason so many have abandoned the games of yore. Monopoly, Candy Land, Mouse Trap, Operation, Uno, Risk — all of these games have fatal flaws. Whether it’s a long game that’s hurt by randomized decisions or a short game with a mechanic that ends up sabotaging quick play, these games have largely been supplanted. This isn’t to say the games don’t have some value, but there are so, so many games that don’t suffer from those fundamental problems. And for many, those flaws have driven them away from enjoying games: the dismay of a sibling relentlessly picking on another, the unhappiness when the dice just don’t go your way — you’ve been there, you get it.

That’s where simple, accessible, modern games come in. These are games that can connect with players without a deep gaming background. They’re games that will invite interaction, but not in a retributive way. There are so many games that foster cooperation, encourage communication, and allow you to think in new ways.

There are many opportunities where playing in-depth board games can be rewarding. I’ve made incredible memories with friends and family playing games that test my thinking and reward me for planning. But even with all that, I’ve made even more memories playing simple games — I’ve made friends with players and become better friends with others. Games have impacted my life, and if I’d limited myself to playing games that really scratched that itch to play something complicated, I wouldn’t have so many of those experiences.

In a sort of fundamental way, that’s why I write this newsletter. I want to help you (and me!) create opportunities to have those same experiences, whatever that form may take. Maybe it’s introducing people to games that push their gaming experiences just a bit past what they were expecting, but in ways that aren’t intimidating. Maybe it’s introducing people to the first game that really opens them up to the hobby. Or maybe it’s just in finding a game to take to a family reunion and play with your grandparents. Games provide those opportunities.

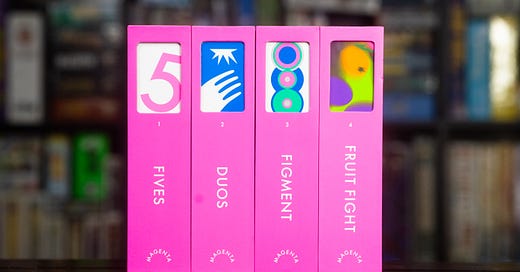

CMYK’s four great Magenta games

This week’s topic wasn’t actually inspired by these games, but they dovetail so well with the topic. Over the weekend, we played through a set of four card games released by CMYK over the course of an evening. People came and went, but Ginny and I played through all four. (I think it’s a total of four different groups — funny how that works.)

These card games, released under the line Magenta by publisher CMYK, all fit right in that perfect spot. They’re games you could explain to a wide array of players, but they’re each interesting and engaging. CMYK has already demonstrated a great knack for that with games like Wilmot’s Warehouse, Wavelength, Spots and The Fuzzies, all games I’ve played and love. Their catalog is generally squarely in my wheelhouse, and these games are no exception.

Fives is perhaps the most curious addition to the Magenta line, but not because its gameplay somehow doesn’t fit. No, it’s actually just because it’s originally a game called Green Fivura. It’s a trick-taking game (you know we’d end up back here at some point, right?) first published in Japan in 2022, and it’s been tough to find since, despite seeing some critical acclaim. The trick-taking here is fairly simple: It’s a must-follow game, and if you win a trick, you’ll collect points equal to the rank of the card you used to win. At the end of a hand, every player whose winning cards sum to a number greater than 25 will gain no points for the round. Simple, simple — except for one thing: the back side of every card is a magenta five card, and you can also play a card from your hand as a magenta five in addition to the rank and suit on its face. Only one player can do it in a trick, though, so you’ll have to find just a good time to use it to its best effect.

This is perhaps the most mind-bending of the games in the set, but it has something going for it that others don’t: If you’re playing with somebody who knows Hearts or Spades, you’ll have a pretty easy time explaining this one. It just might get a little tricky explaining the nuance, but it’s definitely doable. Designed by Taiki Shinzawa. Each game in the line is illustrated by SMLXL.

Duos is, as you might expect, a game about working with another player. You’ll form teams of two, and there will be two or three teams depending on whether you have four or six players at the table. With a deck composed of just the numbers 1 through 8 in two colors, magenta and blue, players will work to complete goal cards by discarding indicated cards from their hand. On your turn, you’ll draw two cards and pass one or two cards to your teammate. The cards drawn are from a public selection of three, or from the face-down deck, and your teammate’s goal card is publicly known.

The game forces you to pay attention to what your teammate is doing on their turn, as you’ll want to pass them cards they can actually use. Maybe their goal card is calling for three cards of the same number — do you know what number they’re going for? They can’t tell you, but if you’re paying attention, maybe you’ll be able to figure it out. The game’s simple and engaging, and a team game without a well-established in-depth meta is always welcome at my table. Designed by Johannes Schmidauer-König.

Figment is a reimplementation of a game I already enjoyed, Illusion, but it turns it into a really fantastic cooperative game. It’s a funny thing — my memory had Illusion as a cooperative game already, but it absolutely wasn’t. Your collective goal is to take a series of five cards with some fun geometric art and organize them according to the prevalence of one color, which is selected at the beginning of the round. On the reverse of the cards, the percentage of each color is listed. It’s a game for visual thinkers — you can’t math your way out of this one. (Probably.) Designed by Wolfgang Warsch.

Fruit Fight, the final game in the line at release, is a fast-paced push-your-luck game all about collecting as much fruit as you can. The deck is composed of a bunch of fruit cards, with each different type of fruit being worth a different amount of points. On your turn, you’ll draw cards from the deck until you choose to stop or are forced to because you’ve drawn a card you already have in front of you. Importantly, when. you draw a card, if anyone has the same card in front of them, you may choose to steal it. For example, if you draw a watermelon card, and there are five watermelons in front of players around the table, you can take them all. And you will. At the start of your turn, cards are turned face-down and put in a scoring pile, but because it’s at the start and not at the end, you will constantly lose valuable cards to your opponents as they push their own luck. Fruit Fight isn’t complex in how it asks you to think about probability. You can do the math if you want to (and if you’re good at card-counting), but most of the time, I suspect you’ll just be drawing a card and hoping you don’t draw a repeat fruit.

This is a Reiner Knizia design that’s been floating around for some 18 years in different forms. The first iteration is Cheeky Monkey, and it’s similar — but there are some important differences, too. This specific ruleset is also published as HIT! and No Mercy. It’s yet another great game in Knizia’s catalog, which is probably large enough now to have gained sentience. Designed by Reiner Knizia.

The collection isn’t perfect. Designer names are simply too hard to find — and while that’s definitely something hobbyists will care about, I do understand it’s not something that makes much of a difference from a mass-market perspective. The boxes are also just bigger than they need to be. Again, I can understand, from a mass-market perspective, why they’re that size — shelf presence and all that. These games ooze shelf presence, with the bright, colorful packages, single-word names, and very modern card designs. I get it. Still, I’d love to see those designers names on the back of the package at the absolute minimum — it’s part of what brings folks into the hobby. “What else has Taiki Shinzawa made?” — that’s the question that can spark that game-changing research.

Still, even with those two imperfections, this is a fantastic selection of games. None of them are wholly new designs, giving this selection a finely curated feeling. Playing through all four in order at a game night actually feels like a natural progression — not in difficulty (perhaps the opposite), but in the way it introduces concepts in board games piece-by-piece. Trick-taking, partnerships, cooperation, and push-your-luck: That’s basically all you need in your personal collection, right? (I kid, I kid.)

Thanks as always for reading Don’t Eat the Meeples! I hope this week has found you well. What simple games do you love to introduce to new people? Have you introduced anyone to the hobby that’s fully embraced it? I know I didn’t just happen on to board games — I was led there by close friends, and some of them journeyed together into our initial forays with me. I was already a great candidate for the hobby. I mean, my friends and I made Risk maps in high school. I wish I’d known how much great stuff was right there, just waiting for me to find it.

Well, until next week, yes? I’m not quite sure what I’ll be focusing on, so if you have suggestions, wing them my way.

Love this sentiment! I just got Fruit Fight in specifically to introduce some friends into the hobby. It's important to have a varied collection.

Simplier games are easy to get on to the table and have everyone playing.

I don't see myself pulling out brass birmingham on xmas day plus teaching the game. I think it's gonna ruin everyone's night