How Dominion changed board games

In introducing deck-building to the masses, Dominion created a genre of both board games and video games.

There are board games that have had significant impacts on the hobby. Some games find mass appeal and break through, like Ticket to Ride and Catan. Some attract wide attention in the hobby, like Pandemic Legacy. Some games have made significant impacts beyond board games — and that’s where we are this week with Dominion.

This is a new series I’ve been planning for a bit about games that changed the course of board gaming. I’m planning a new entry maybe once a month at most, but probably closer to every quarter. I’ll try to go into some depth about these games, focusing less on strategy and more on historical context. I’ll try to find contemporary opinion to demonstrate how games have changed. If you have any thoughts on games that truly changed the course of board gaming, I’d love to hear them.

With that said, let’s get to the fun.

Few games have had as broad impact on the games industry as 2008’s Dominion. The now-classic Donald X. Vaccarino game is often claimed to be the first deck-building game, and while that claim has been disputed and largely disproven, there’s also some merit to the idea, too.

Before we get to that claim, we would be well-served to define what’s meant by deck-building. It’s a term that’s easy to toss around, but a lack of definition will make sussing this out difficult. Geoff Engelstein and Isaac Shalev define deck-building in Building Blocks of Tabletop Design as follows:

Players play cards out of individual decks, seeking to acquire new cards and to play through their decks iteratively, improving them over time through card acquisition.

In Dominion, you’ll be acquiring cards from a limited set. There are just 10 ‘kingdom’ cards you’ll be picking from in any given game, in addition to cards included in every game, money cards and victory point cards. Each game has you pick 10 of the 25 available card types.

The idea that Dominion was the invention of deck-building is understood by now to be factually inaccurate because of the release of one StarCraft: The Board Game, which arrived on the market a year earlier. Zee Garcia, who you may know from being a member of The Dice Tower (though this predates his involvement there by several years), pointed that fact out in 2008 in a BoardGameGeek forum post. Reports of reports (I couldn’t find the primary source) have mentioned this having been a case of parallel ideas coming together, which feels believable. Interviews with Vaccarino have his initial design coming in 2006, a year before StarCraft’s release.

This distinction is perhaps not important, but I think there’s value in tackling this question early. If we’re to talk about the impact of Dominion, understanding the sources of its innovation will show more fully how that played out historically.

Dominion, of course, didn’t spring from nothing fully formed. Vaccarino is understood to have been an avid Magic: The Gathering player, a game whose influence is still being felt in ways both positive and negative. (The game tends to be great; the glut of releases and the clear cash-grab nature of the game now, less so.) The influences from Magic are easy to understand, with the 1994 collectible card game being easily one of the best deck construction games to have been designed. Dominion takes the idea of deck construction and inverts it — rather than constructing your deck, then playing the game, you instead construct your deck as you play the game. It’s an important distinction, and that one twist is an important one.

Contemporary opinion was swift and near-universally positive. The Awards and Honors section on BoardGameGeek is as long as it is for any game I’ve seen. The highlight, of course, is the prestigious Spiel des Jahres prize in 2009, for which Dominion beat out the now-classic Pandemic. It received the Mensa Select prize. It won Game of the Year in the Golden Geek awards. This was a game that made immediate waves and was hotly anticipated.

In 2008, BGG user Jonathan Franklin spoke highly of the game.

The game as played by the rules is very good and like a potato chip, you can't play just once. At the same time, Dominion is really a system. All sorts of ideas will float into your head about other possible cards. Given the creativity of the designer and developers, I have little doubt they have thought of some of your ideas too.

16 years ago, Dominion was a massive hit in the still-young board game scene. While it lacks the hotness quality of a game released in the last year, it remains a considerable influence on gaming. Both Dominion and Dominion: Second Edition, as well as Dominion: Intrigue, are firmly in the top 200 games on BoardGameGeek.

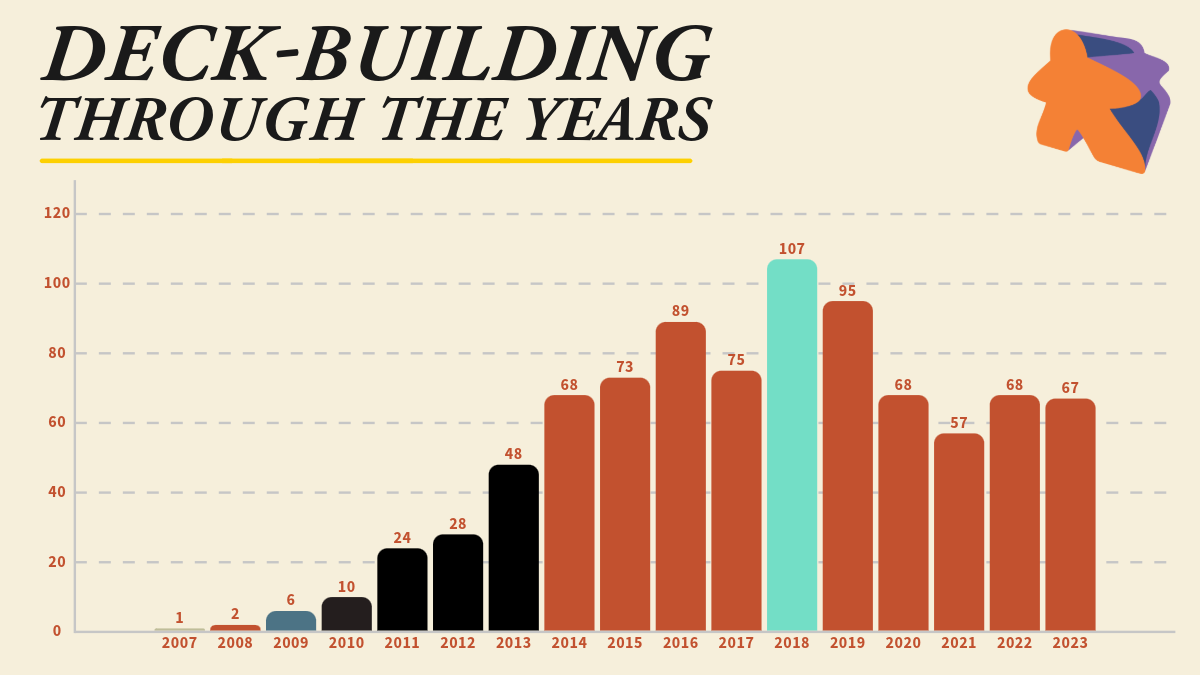

In the immediate aftermath of Dominion’s release and success, the genre grew quickly. In 2009, six games now labeled as ‘deck, bag and pool-building’ were released. One of those was Dominion: Intrigue, a standalone expansion to the original, which was joined by the expansion-only Dominion: Seaside. It was joined by several games that saw some success: Thunderstone, Arctic Scavengers, and Tanto Cuore. Each of them took deck-building in a slightly new direction, but none saw the same level of success. Of those three, only Tanto Cuore, whose slightly dubious provocative-anime-maid theme garnered it a unique audience, have had a version released in the last decade.

2010 saw the first release of a game with “deck-building” in the title — not Ascension, which became Ascension: Deckbuilding Game in its 2014-release third English edition having been renamed from its 2010 name of Ascension: Chronicle of the Godslayer — but Resident Evil: The Deck Building Game, which was not highly regarded. The growth in 2010 of the genre was becoming clear, though, with another Tanto Cuore standalone game and two more Dominion expansions (Prosperity and Alchemy).

2011 saw the number of deck-builders released double. The extremely well-regarded Mage Knight integrated deck-building into its hours-long gameplay. A Few Acres of Snow took the mechanic into a two-player wargame setting. The IP-themed games started rolling in, too — Star Trek: The Next Generation Deck Building Game still remains one of my favorites. Friday put deck-building into a solitaire context. It also saw the first “dice-building” game, Quarriors, hit the market, where players gained additional dice into their dice pools.

More and more, we saw games hit the market that integrated deck-building in novel, interesting ways. 2012’s Legendary: A Marvel Deck-Building Game took the mechanism in a cooperative direction. 2014’s Star Realms added a slightly more chaotic card-selection idea, giving players an opportunity to build something that ends up pretty unique. 2016’s Clank! A Deck-Building Adventure added a board players move around as they attempt to avoid making too much noise. Harry Potter: Hogwarts Battle added a cooperative campaign.

Further, we saw the mechanics of deck-building being abstracted away from simply dealing with decks and cards, moving into dice-building and bag-building. 2013’s Orleans added worker placement and bag-building to the mix, with your workers going into a bag to be pulled out at random. 2018’s The Quacks of Quedlinburg gave us push-your-luck bag-building. Both of these present the deck-building concept in a different way, but the essence is still there: Gain new resources (tokens or workers rather than cards), shuffle them (in a bag this time! Way easier!) and select some from the bag each turn.

Distilling deck-building into its core conceit — over the course of the game, improve your personal selections — has given the mechanics life beyond Dominion. Of the top 100 games on BoardGameGeek, 18 of them include the mechanic Deck, Bag or Pool-Building.

We’ve even seen deck-building inverted: Emma Larkins’ 2020 release Abandon All Artichokes is lovingly called a “deck wrecking” game, as your goal is to rid your deck of, as you’d expect, all the artichokes it starts with. In Dominion, that’s trashing, and it’s an essential part of achieving success.

Trends in board games have generally been indicative of larger trends in gaming —cooperative board games and couch co-op video games sharing some DNA, for example — or they’ve come from video games into board games — point-and-click adventures or 4X strategy — or they’ve rarely influenced each other too much — can you think of a worker placement video game? Me neither.

But something interesting and unique happened with deck-building.

The Roguelike deck-building video game phenomenon

In 2019, Slay the Spire released officially on Windows, Mac OS and Linux, following a successfully early access period on Steam that lasted just over a year. The game’s concept is more than just familiar to board game players: Each game, you start with a very basic deck, and over the course of the game, you’ll purchase cards that improve that deck. Rather than happening during turns, that’s happening between battles against enemies, and your cards will help you in battle with those enemies. The Roguelike portion comes through a procedurally generated map you’ll progress through, and if you die, you’ll start at the very beginning next time you play.

Dubbed a “Roguelike deck-builder,” Slay the Spire was gaining traction in a big way. It wasn’t the first one — Coin Crypt is generally regarded as having that claim — but it was certainly the most successful. It’s gone on to sell over 3 million copies on Steam, and given it’s on Nintendo Switch, Xbox One, Playstation 4, iOS (even available in Apple Arcade) and Android, those numbers certainly reach significantly higher. (Sales numbers of board games are more difficult to find. In 2017, reports had Dominion at 2.5 million sales. What is it now, I wonder?) That particular genre of video game has continued to climb, and it’s a well-understood term in the scene.

Of course, the story wouldn’t be complete without talking about Slay the Spire: The Board Game, an adaptation of the video game in a physical form factor. There’s a certain humor to the circular qualities here, and while I think it’s quite cool what they’ve been able to achieve with the property, I do wonder if a $120 adaptation of a video game you can score for under $10 will be a runaway success. (See also: Stardew Valley: The Board Game.) While much work appears to have been done to make it a successful board game, reducing some of the overhead you’d expect from a one-to-one adaptation of the video game, that’s still a steep price tag.

Roguelike deck-building video games have continued down this path, though I must admit to having mostly played Slay the Spire. (A project for another day, it would seem.) It makes one wonder what other sorts of board game mechanisms could lend themselves to a digital world so effectively. Are we in for real-time strategy worker placement? (I don’t think so. Maybe?)

Thank you, as always, for reading Don’t Eat the Meeples! If you read last week’s issue until the end, you’ll have learned that I’m dreadfully close to reaching 500 subscribers. There’s a very, very real chance that happens in the next few days. Thank you all for your continued readership and engagement — I truly appreciate it!

As I said last week, if you’re interested in helping me celebrate this milestone and would like me to send you a Don’t Eat the Meeples sticker or two for free, please reply to this message or send me a DM on Substack (or another place you follow me, if you’d like) including your name and address. I’ll have those sent off once I reach that 500 mark. It’ll be a momentous day.

Here’s to a good week of gaming!

Dominion really is a great game and holds up as the standard for deckbuilding games in my opinion.

Interesting thought on board game mechanics making their way into video games. I sort of already consider RTS video games to be similar to worker placement board games, although I'm not sure which came first and I don't think one was inspired by the other.

Good piece! But not sure why coin crypt would be considered the first roguelike deckbuilder when Dream Quest was both before it, as well as much more influential on StS etc.?