Five games to play at a family game night

These five games offer a different perspective on games for groups.

If you search around for ‘games for families’ (especially in this newsletter), you’ll find reams of recommendations for games for 3 to 5 players, or you’ll find recommendations for party games for larger families. Those are great — I love a good party game, and I love a game that’s broadly accessible.

But I ran into something the other day that gave me some pause. We were playing games with an aunt and uncle of my wife’s and their four kids, all of whom are in the perfect age range for playing games. It’s a common activity when we visit (and we visit often), and it’s not at all like I’ve struggled to find games for that crowd. But I wanted to bring over some games that the entire family — including the two of us — would be able to get to the table, bringing the total to 8. A party game just wasn’t what we were looking to play, as much as they love playing games like Werewolf and Spyfall. I wanted to bring over something a bit different — not a strategy game, per se, but something that wasn’t focused solely on social dynamics.

We ended up playing several rounds of Ito, a tremendous game first published in Japan that’s just starting to see a wider release. We’ll talk about Ito in more depth when the time comes here, but it felt so much like Wavelength and The Mind have merged somewhat gracefully in a transporter accident, creating something altogether new and unique.

These seven games offer something different for larger families, but they’re just as good for a game night with players who aren’t looking for deeply strategic games. They all play at least 7 players (barring one — Things in Rings — but I think I have some thoughts there, too. We’ll get there), as I’m looking for games here that work well for large groups.

Hey Yo

2–10 players

If you thought rhythm games were confined to video games, Hey Yo is here to upend your expectations. Published by Oink Games, this is basically exactly what you’d expect if I told you I was bringing a “real-time cooperative rhythm game” to your house. While you play the game, an included noise-making device is playing a rhythm interspersed with little beeps. When you hear the beep, the next player in the rotation must play a card from their hand. They can play any card, but what they choose will considerably impact the team’s success. If a card isn’t played on time, the team is penalized.

Of course, if it were as easy as simply dropping a card on the table at the appropriate time, there wouldn’t be a whole lot of challenge to the game. Instead, you’re building a music track to the beat, with each card featuring two tracks with sounds on them. You earn points for building long chains of a single sound, but playing cards in the right place at the right time, especially when you have very few options, gets pretty difficult.

This newsletter is packed to the brim with weirdness, and I think you’ll see that as you progress here. Hey Yo is probably the most unusual game on this list, but it works really well. The frenetic action takes a game that’s not heavy on strategy and turns it into a unique experience.

Designed by Takashi Saito, published by Oink Games. Hey Yo plays 2 to 10 players.

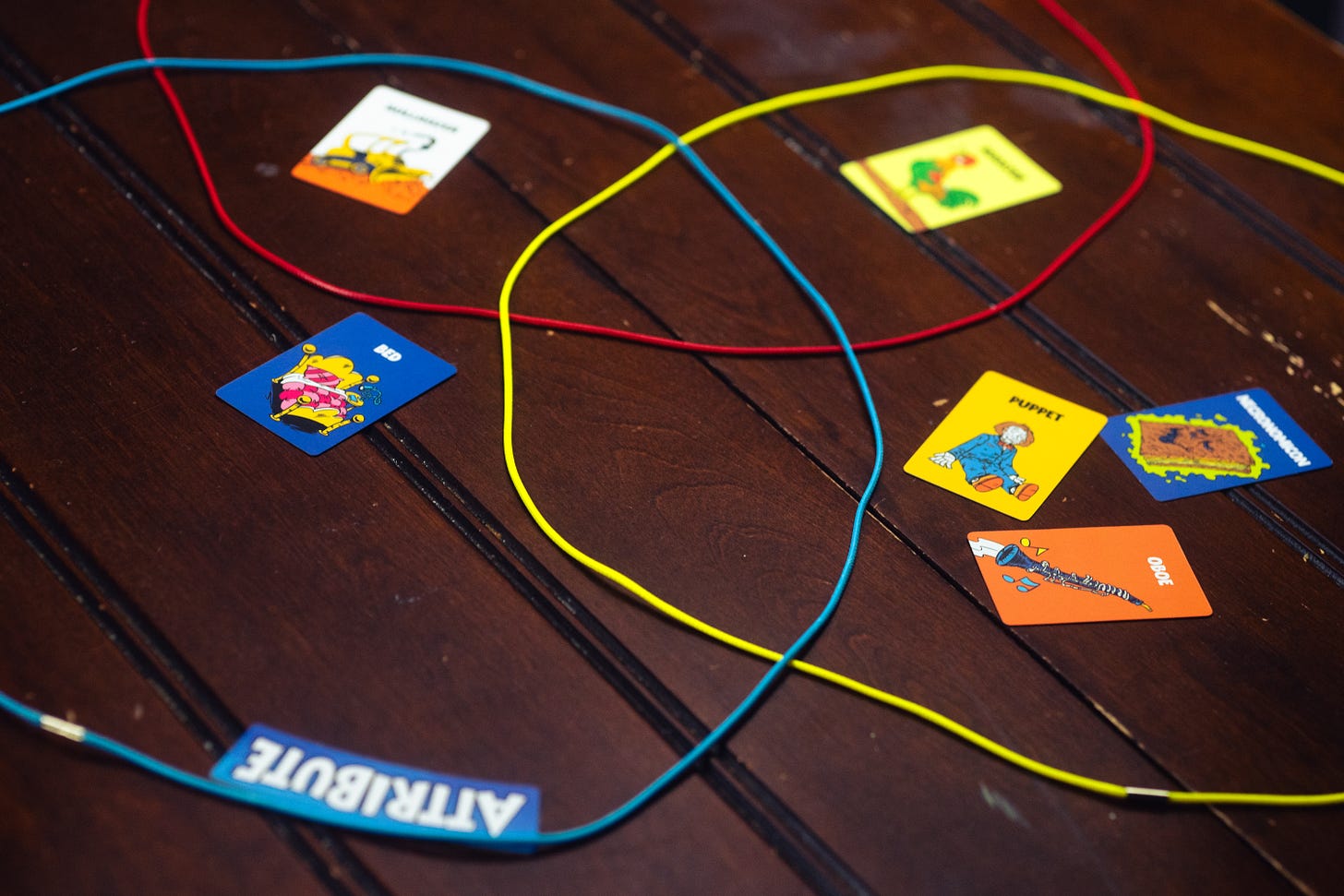

Things in Rings

2–6 players

This is the exception I noted in my preface, but I think I can justify its inclusion here. Things in Rings is a game of making Venn diagrams. It’s weird. There are a lot of kind of weird games here this time around. (Maybe that’s saying something about me, or maybe it’s saying something about the player count. I dunno.) This game sort of masquerades as a party game, which I think is largely because it’s certainly on the light side of the weightiness scale.

The game is structured around anywhere between one and three rings, depending on the desired difficulty, each of which represents a specific concept. Players will be placing cards from their hand in different areas of the rings or outside of the rings entirely, and one player — the knower of the rings — will tell that player whether they’re right about its placement or not by moving it to the appropriate place or leaving it as-is. (Tangentially, how do you all feel about Rankin and Bass’s Return of the King? I heard “the bearer of the ring” sung in my head after I wrote that phrase, and it’s a pleasant memory.) Throughout, you’ll be trying to figure out what each of the rings represents, because any time you place a card in the correct location, you’ll get to place another. When somebody runs out of cards, they’ve won.

Cool, right? I hope it sounds cool and not like a school exercise, because if I’ve shown it as school — well, I’ll have missed the mark somewhat. I do think you have two options if you want to fit more players here. The first is to simply play the game with an extra player or two, accepting that it will take longer. Maybe you can just reduce the number of cards with which each player starts. But there’s one more great option — the game very easily translates to a cooperative variant, which is included in the rules. I’d suggest giving that a try, and if you need to fit one or two extra players in there, it’s not much of a problem.

This is a game I’d love to explore more. I do feel like I’m pretty miserable at it, but I won’t complain about that.

Designed by Peter C. Hayward, published by Allplay. Things in Rings plays 2–6 players.

Ito

2–10 players

You know when you play a game and the experience is just kind of surreal, like it’s a game that maybe you didn’t expect to work as well as it does? That’s Ito. It’s a game that released in Japan all the way back in 2019, and it’s steadily been gaining steam in English-language gaming communities. It’s really best described as the metaphorical child of The Mind and Wavelength, both of which are unusual, excellent games. If you just sort of smashed them together, I don’t think you’d get Ito. That’s the interesting thing about this game — it’s more than the sum of its parts, and it’s importantly different than that sum.

In Ito, you and your teammates each draw a number from a deck of cards numbered 1 to 100. You can’t reveal what you’ve drawn. One player will draw a topic card (or decide a topic) and read it aloud — that’s the spectrum through which you’ll be thinking about your numbers. One by one, players will give a hint as to the number of the card by describing something.

By way of example, let’s say the topic was about vehicle speed, with “slowest vehicle” at 1 and “fastest vehicle” at 100. If I had, say, a 1, I might say “a car with no wheels,” and at 100, I might say “the Delta Flyer when Janeway and Paris break the transwarp barrier and turn into a weird salamander-like creature.” Everything else would fall somewhere else in the middle. Maybe if I had 20, I’d say “a very fast e-bike.” It really depends on your group, and that’s what makes this such a perfect game for families. Unlike The Mind, which permits no communication at all, you’re encouraged to talk about your answers or even change your answers during discussion.

This really is an interesting game, and I’m a big fan. Weirdly, I didn’t think I would be. I mean, I love cooperative party games as much as the next person, but there was just something that made me wonder about its feasibility. I am quite happy to admit I was mistaken.

Designed by 326 (Mitsuru Nakamura), published by Arclight Games and Arcane Wonders. Ito plays up to 10 players, but I think you could get more in there.

Gussy Gorillas

3–10 players

One of the stranger games I’ve played over the last year is Gussy Gorillas, a real-time negotiation card game in which you can’t see the cards in your hand. The only reason you have any idea whether you might have something good in your hand is because the whole game is structured around players making offers to you for those cards, and if the card’s good enough or fits their hand well enough, they might offer you enough to convince you the card’s good. Once you negotiate successfully for a card, you’ll get to keep it. You can also choose to keep a card. If you’re trying to negotiate by offering a card and not getting bites, you can even sweeten the deal by offering more cards.

The cards with which you’re negotiating are generally just numbers, with a few exceptions that we’ll address later. Those cards are just numbered one through seven, as well as 10, -8 and -12, and they largely just score points based on their rank. If you end up with a pair of numbers at the end, they won’t score, which might be nice if you’re dealing with a -12 or -8, but would be less desirable with, say, a 10. That forms the basis for negotiation, as you might imagine, and it’ll provide you the best opportunity at discerning what’s in your hand.

That’s an interesting enough framework, but I promised there was something more, and it’s what makes the game work. There are three different types of special cards shuffled in. A split allows you to divide a pair into two separate scoring cards, rather than the two being canceled out. A flip allows you to turn a card upside down — so a 6 becomes a 9, a 7 becomes a 2 (it’s a fancy seven!), and a 10 becomes a 1. Finally, a reverse turns a negative number positive and a positive number negative — flipping that sign can be brutal, or it can be glorious, depending on how it’s used.

Gussy Gorillas. Weird game. I like it, but because it’s played in real-time, you’re sort of always in a half-shout standing up from the table trying to be noticed. That’s even more clear with more players. It’s wild and fun, but it’s not for every group.

Designed by Nick Murray, published by Bitewing Games. Gussy Gorillas plays 3–10 players.

Bohnanza

3–7 players

We’ll end this week with a true and utter classic. Bohnanza, crafted by one of the great designers, Uwe Rosenberg, is a trading and negotiation card game in which you’re growing beans and selling them. This classic game of bean-trading supports up to seven players, and at that player count, it remains interesting and compelling — a difficult feat.

In Bohnanza, you’re dealt a hand of cards, and you can’t reorder those. On your turn, you must plant the first bean card in your hand in one of your two fields, and you may optionally plant the second one. You’re restricted in that way: You start the game with just two fields (and can later buy a third field), and you can only plant a single type of bean in a field. If you have to plant another type of bean, you’ll have to sell the beans you have in your field. But here’s the thing: It’s not a one-to-one ratio. Different types of beans are more or less common, and the more rare the bean, the easier it is to sell them for maximum profit.

It’s not just about figuring out the appropriate timing to sell beans, though. On other players’ turns, you’re free to negotiate with them. You can trade cards in your to them for cards in theirs — a keen way to make sure you’re not forced to sell your beans prematurely is to get the cards out of your hand before it’s your turn. Considerations like that make Bohnanza an interesting negotiation game, because you’ll often find yourself offering up cards you might want later — you’re sort of negotiating with yourself.

Designed by Uwe Rosenberg, published by AMIGO. Bohnanza plays 3 to 7 players.

Honorable mentions

Point Salad (6p) is a set collection game in which your cards are either members of sets, or they’re the scoring cards. If it played just one more player, it would have made the list. Designed by Molly Johnson, Robert Melvin and Shawn Stankewich; published by Alderac Entertainment Group.

No Thanks! (7p) is one of my all-time favorite push-your-luck games, and it fits the right number of players — but I also featured it last week, so I’m skipping it this time around. But you can read what I wrote about it in Eight games to replace Exploding Kittens if you’d like to check it out. Designed by Thorsten Gimmler, published by AMIGO.

Just One (7p) is a cooperative party game that’s just a little too party-oriented for my purposes here. Sure, maybe Ito counts for that too, but it doesn’t have to. Designed by Ludovic Roudy and Bruno Sautter, published by Repos Productions.

Wavelength (12p) tips again toward being a party game, but it’s a really great one — can you figure out what your teammates are thinking? This game also has a really big dial. Neat! Designed by Alex Hague, Justin Vickers and Wolfgang Warsch.

Thanks, as always, for reading Don’t Eat the Meeples. I hope you can find some opportunities to play games with family over the next few weeks.

Next week: The 2024 board game gift guide!